Renzo Piano’s Architectural Legacy

Born in the coastal city of Genoa, Italy, in 1937, Renzo Piano grew up with a yearning for discovery – to voyage beyond the mysterious Mediterranean and return with a legacy. And indeed, a legacy he forged. But before he became the renowned architect we know today, he was the son of a builder. Captivated by the magic of construction on his father’s sites, he watched as structures seemed to effortlessly rise out of thin air. In a post-war era, when rebuilding symbolized hope and resilience, these early experiences instilled in him an appreciation for the beauty of construction and the art of detail. Perhaps it was this foundation that shaped his distinctive visual language, which calls attention to the otherwise easily unnoticed details of a building in unique ways.

1977 - The Pompidou Centre: Piano’s Early Radicalism

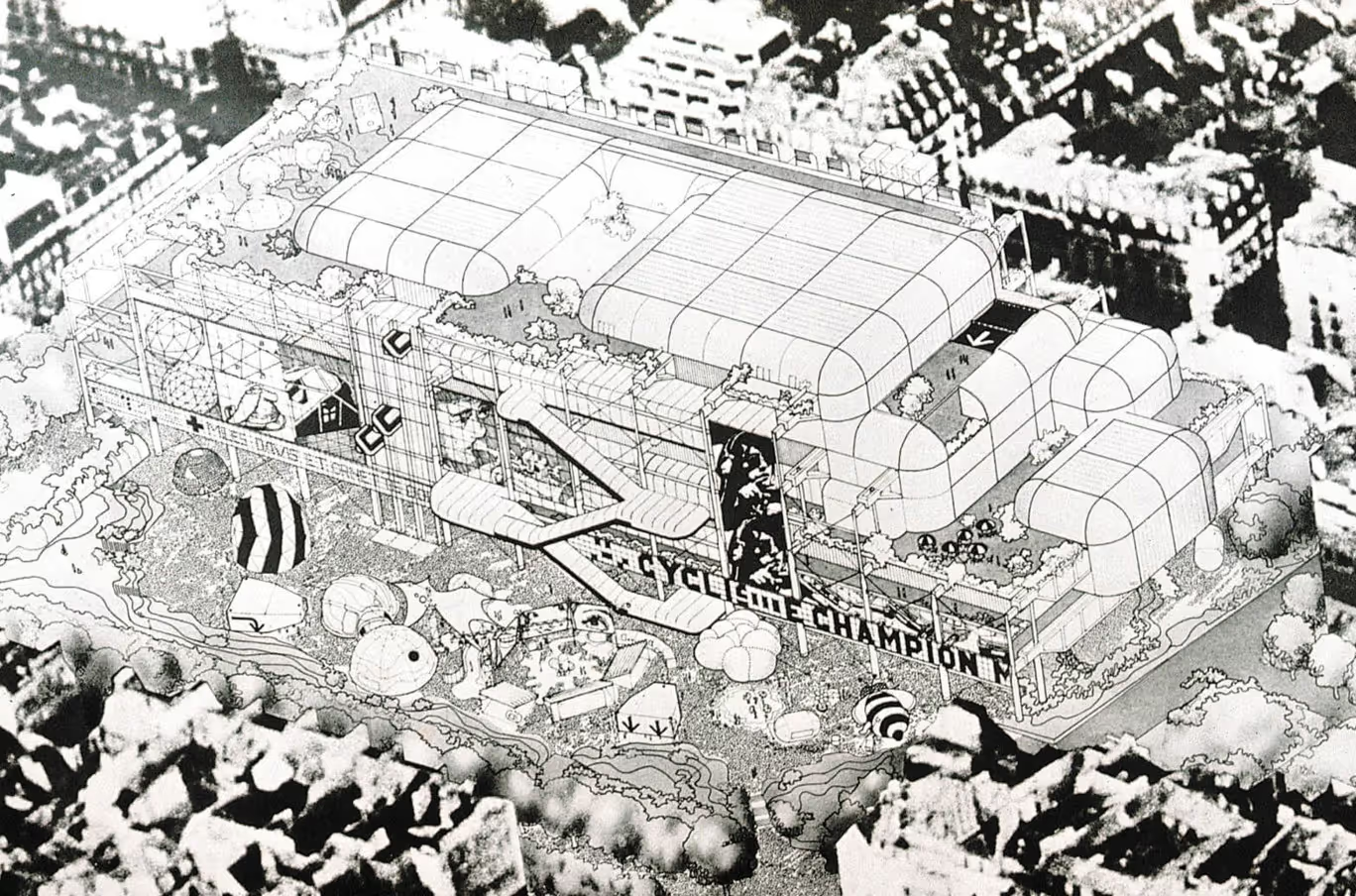

In 1971, when Georges Pompidou announced an international competition for the new French National Museum of 20th Century Art in Beaubourg, the young architect, alongside his new design partner Richard Rogers, began sketching ideas and assembling collages. Little did they know, this project would not only define their careers but also set the stage for pioneering architectural movements that would reverberate through the following decades, ultimately propelling them onto the international architectural stage.

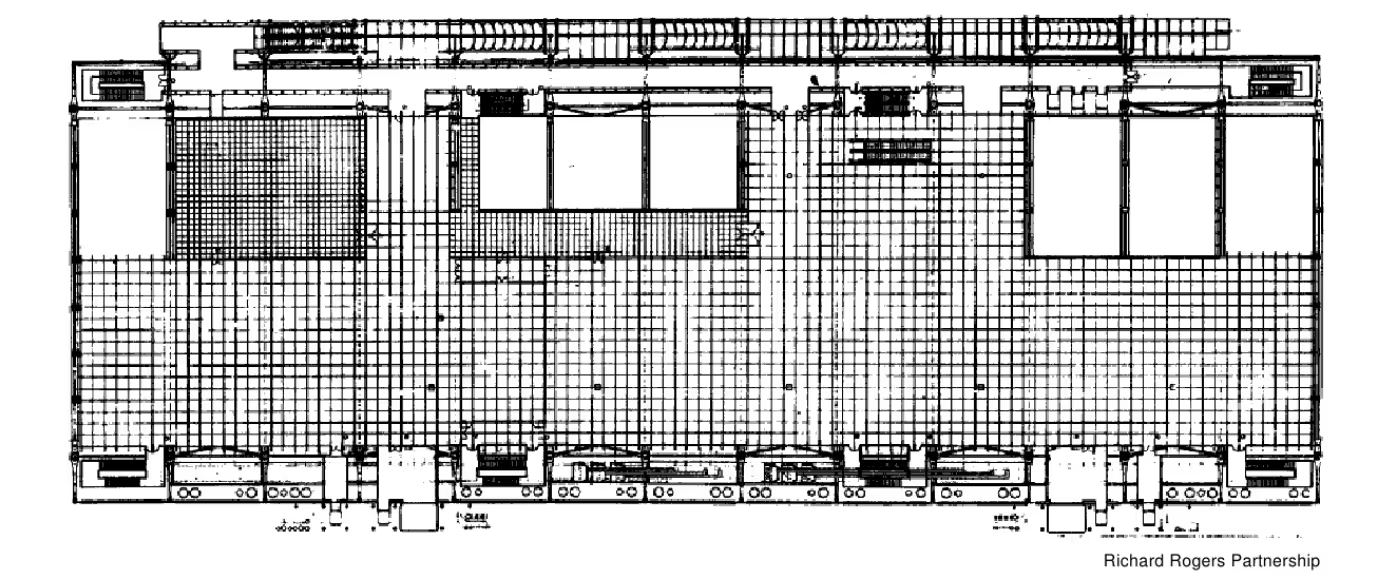

This icon of a new architectural era, now known as the Pompidou Centre, stood out in the city of Paris for many reasons. While buildings of ‘skin and bone’ usually hide their unappealing skeleton with beautifully painted or meticulously clad facades, the Pompidou was a building turned inside-out – with steel beams, conduits, and escalators shifted to the building’s exterior. The building’s facade became a spectacle of brightly color-coded pipes and ducts, each color marking a different function: blue for climate control, green for plumbing, yellow for electrical systems, and red for movement, such as elevators and escalators. This color-coded system transformed the functional infrastructure into a vibrant visual language, making the building itself, as Piano calls it, a “big urban toy” of the city.

In this project proposal, Piano and Rogers viewed the city itself as their client. They believed that for a constantly evolving urban environment, a monument as significant as the Pompidou, must be designed to adapt over decades. To achieve this, they extended the concept of flexibility to every component of the building, creating a structure in which interior spaces could be reconfigured at will, while exterior pieces could be attached or removed as needed throughout the building's lifespan. The outcome was a five-story structure, free of internal interruptions by traditional services or circulation elements. Corridors, ducts, fire stairs, escalators, lifts, columns, and bracing—elements that would typically intersect and fragment each floor—were instead moved to the exterior, leaving large open public spaces within, for the city to enjoy.

The visual narrative of the Pompidou Centre goes beyond mere functionality to make a bold aesthetic statement, breaking the concrete molds of traditional modernism. It stands as an example of how standardization and restrictive construction methods don’t have to limit the spirit of discovery and innovation. Collectives like Archigram and Superstudio responded to these modernist ideals too with unorthodox, often ambitious speculative designs, pushing the boundaries of what architecture could represent and achieve. Influenced and inspired by each other, the Centre became a part of a movement that sparked a widespread reaction against the brutalism of modern architecture in the 1960s and 70s.

1987 - Menil Collection: To Build as a Gesture of Peace

For Renzo Piano, designing a good building is a civic gesture – it’s a gesture of peace.

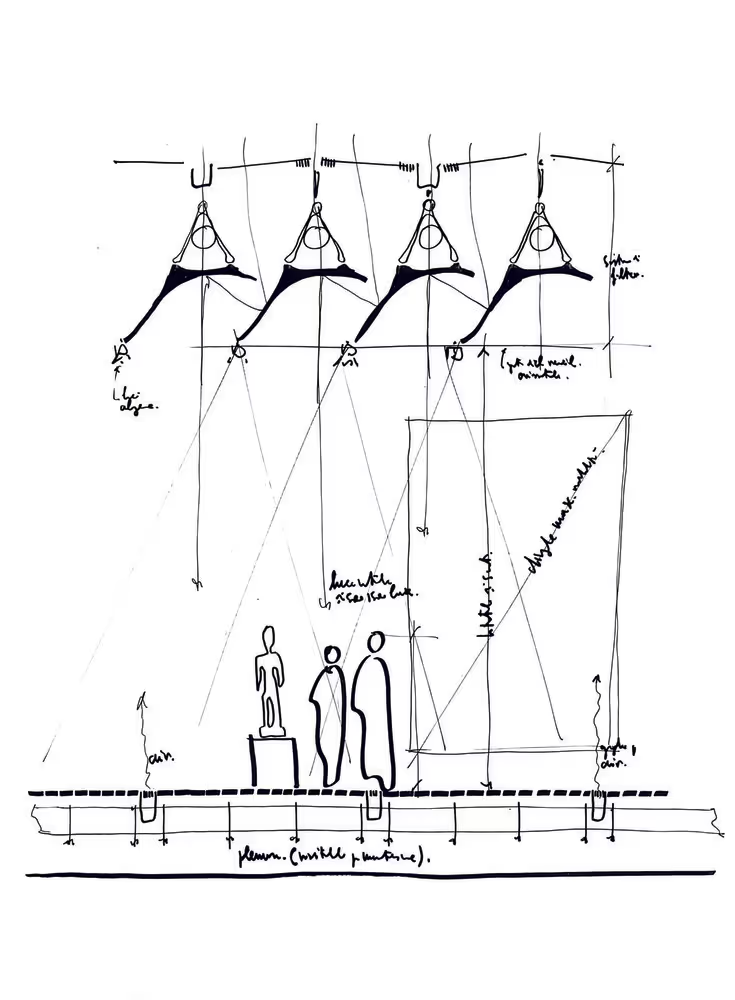

Ten years after the Pompidou Centre, Piano made his American debut with the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. At first glance, this building seems a world away from the bold Pompidou, but a closer look reveals familiar hallmarks like Piano’s meticulously engineered roof system and his thoughtful design of served and service spaces. Here, however, the structure humbly integrates with its surroundings. Its intimate scale and recognizable materiality were carefully chosen to preserve the neighborhood’s character, blending seamlessly into the community. The museum is not immediately identifiable to an outsider, yet for locals, it’s as familiar as the park beside it.

Piano conceived the roof of the art gallery as a series of concrete 'leaves', tailored to softly filter the intense Texan sunlight and create an airy openness throughout the space. With an interlocking truss of triangular modules, each secured by simple nuts and bolts, and a steel framework holding glass panels that double as a discreet rainwater channel, Piano once again hides structural ingenuity in plain sight.

1998 - Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center: Architecture for the People

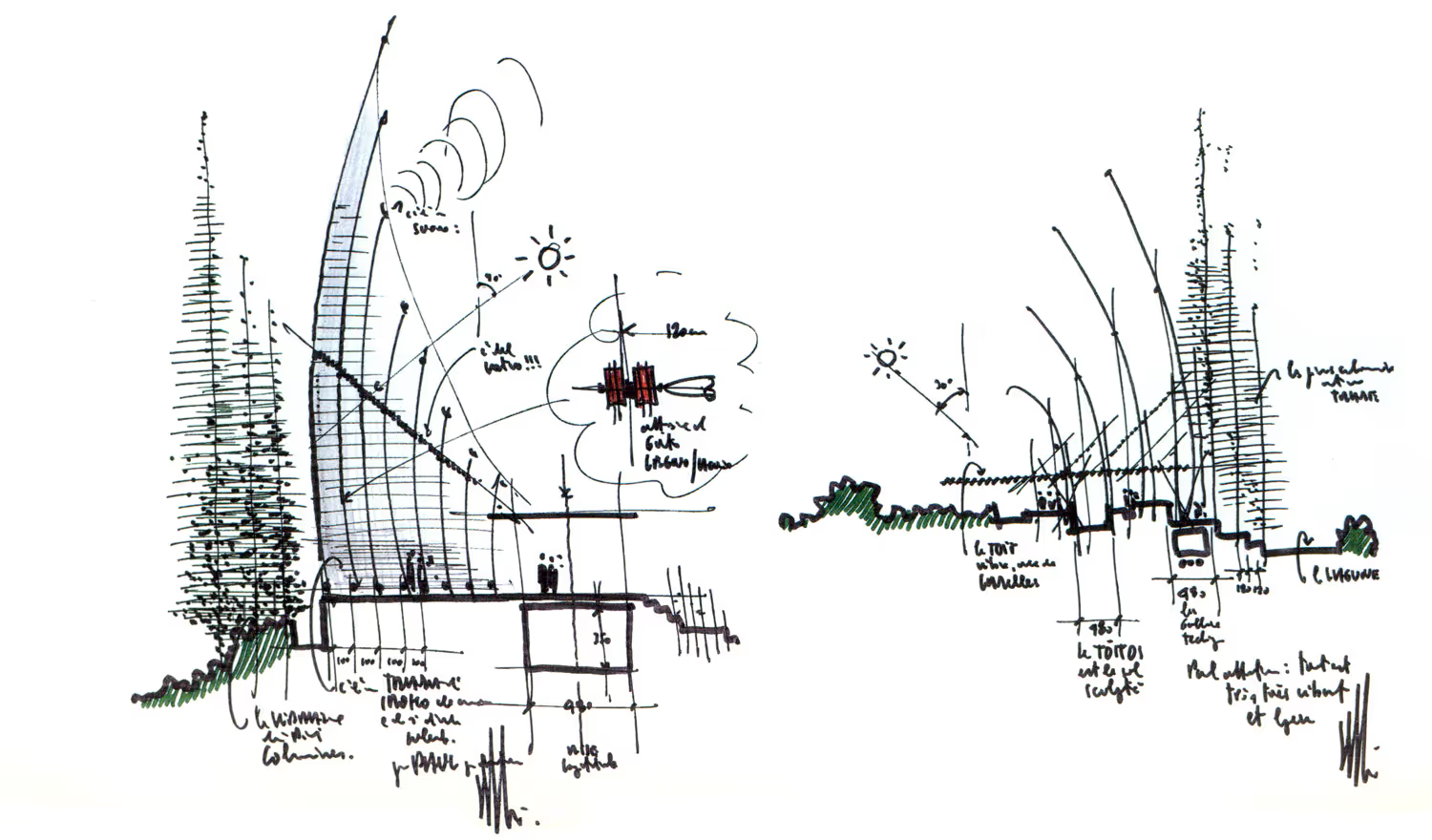

When Renzo Piano was selected to design the Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center, he envisioned a structure that would bring more than just international attention to the pacific islands of New Caledonia. Drawing inspiration and technology from traditional Kanak houses, Piano made the site and environment the design drivers of the project. With an objective of blending modern materials like glass, aluminum, and steel with traditional ones such as wood and stone, he found new ways to respond to this site.

The center’s design takes the form of a cluster of "huts" or the towering, curved shells that look much like traditional Kanak huts except instead of traditional woven vegetable fiber, these buildings are made of ribs and slats of iroko wood. Working on a culturally and politically sensitive site, Piano —an outsider —creates a visual language through structural detailing that has an unfinished and evolving aesthetic almost like a building under construction, subtly reflecting his role as an architect in the project to act as a vessel for the Kanak people's resilience and history, leaving room for their future transformation.

This thoughtful approach in both innovation and contextual sensitivity later became recognized as part of the celebrated ‘Bilbao Effect,’ as the project’s significance resonated globally, highlighting architecture’s power to uplift and honor cultural identity.

2012 - The Shard: A Harmony of Form and Function

When talking about Renzo Piano’s iconic architecture, it’s impossible to overlook The Shard in London. Responding to the city’s push for sustainable, high-density development, this mixed-use tower rises above London Bridge Station as a vertical city, blending work, living, and leisure spaces into a single, dynamic structure.

Here was a project that showcased Piano’s mastery of light through innovative technology and design. The intricate double-skin facade, and automatic internal blinds, adeptly controls daylight and heat, adjusting seamlessly to the shifting daylight enhances the energy efficiency of the building.The intentional 'fractures' within the facade facilitate natural ventilation for winter gardens, highlighting Piano’s skill in harmonizing technical rigor with creating a sense of place.

Each of these buildings embodies Piano’s vision of architecture as a gesture of peace. By harmonizing with communities, respecting cultural roots, and embracing sustainable design, he crafts spaces that stand as his gifts to society—uniting people and place with quiet, enduring purpose.

2018 - The Krause Gateway Centre: A Pinnacle of Piano’s Principles

The final project in this journey is the Krause Gateway Centre – a six-story headquarters for Krause Group Associates designed by the Renzo Piano Building Workshop, in collaboration with OPN Architects. This innovative structure embodies Piano's legacy of architectural philosophy of open-plan systems, play of light, and responsive design all in one building. Reflecting Krause Group's passion for collecting art, the building serves as an unusual yet compelling intersection of an art gallery and a corporate office.

In an exclusive webinar hosted by Snaptrude titled ‘Architecture that inspires’, OPN’s Principal Architect, Danielle Hermann shares shares her insights on their collaboration with Renzo Piano Building Workshop for the project:

“A lot of times we get asked the question, is this a corporate headquarters that functions as an art gallery or is this really more of an art gallery that has a corporate headquarters built into it? The fact that people have to ask, because you kind of can’t tell, is actually great. That means we succeeded, because it has a feeling of being both at once.”

- Danielle Hermann, Principal at OPN Architects

Sitting at the crux of the city’s shifting grid, this 160,000 sq ft of area programmed across six floors, derives its iconic form from a response to this urban grid. The characterizing 16-degree rotation of the uppermost floors aligns with the northern city grid, while the lower floors maintain continuity with the surrounding urban context to ensure the building is not a barrier but rather a literal two-way street between the two roads its form would otherwise interrupt.

The building's transparency and openness reflect Renzo Piano's enduring commitment to fostering connections between people and their surroundings, inviting public interaction while maintaining a sense of community within its corporate space.

To explore the design, check out the model on Snaptrude for a detailed visualization of the Krause Gateway Centre here.